What if we imagined what we usually call “healing” as “building” or “rebuilding?” Ania Garcia suggests and analyzes this shift in language by imagining survivors as architects. She highlights important concepts of inside and outside with regard to our minds, bodies, and our physical place in the world around us. Deeply thoughtful comparisons and illuminating, life-affirming connections help us imagine our own architectural powers to build new, beautiful homes.

Architecture of Intimacy

by Ania Garcia Llorente

There are experiences that reverberate the main structure of our consciousness, subwoofing the interior of our being. In these cases, there is no punctual affectation, but a vibration that penetrates inside and avalanches itself over time. Here the subject doesn’t realize until later of all the destruction caused, pieces of debris are found along the way. A single experience could disarticulate the fundamental set of beliefs and understanding of our life. We could lose the sense of intimacy, the state of tenderness and our ability to trust ourselves and others. Personal intimacy is as fragile as it sounds; it could be destabilized or destroyed after a single event of abuse. When that happens, the old notion we had of it no longer makes sense, and we need to rebuild it using other mechanisms that would now have to include the memory of intense frustration.

The process of recovery after trauma is sometimes described as healing. This notion characterizes it as a disease, where there is a wound that needs to be closed by medical or shamanistic assistance. For some situations, this translation of the trauma as a wound could become very problematic. First, it locates a complex process in one single imaginary place, disconnecting it from the other aspects of our life that are being affected by it. On the other hand, it implies that it requires a treatment in the form of certain luminous magic, that for some people, may not be real in the first place. For certain traumatic experiences, I personally prefer to use terms that come from construction and architecture. This is to define recovery from a more active approach that also avoids a state of victimization. If intimacy and tenderness need to be rebuilt, I must find the tools to do it. But first, How do we rebuild an interior space?

As an architect of my own internal world I understand that any generic notion of it would not be accurate. I think we have to even make the tools to build it. It is all entangled with our particular means of survival, desires and stubborn conventions. Interior space could be as limitless as our imagination, but it could not exist if we don’t think about how to build it. But wait, How to behave within ourselves?

People don’t always figure out how to speak to themselves, how to deal with external abuse, and most importantly, how to daydream. In his book The poetics of space, Bachelard mentions daydreaming as essential for intimacy, since it is a way of understanding and valuing ourselves. I agree that we cannot value ourselves just by reading the facts and the memories of our previous experiences. Imagination is needed. Personally, I think of intimacy as a hard-boiled egg that slowly mutates over time:

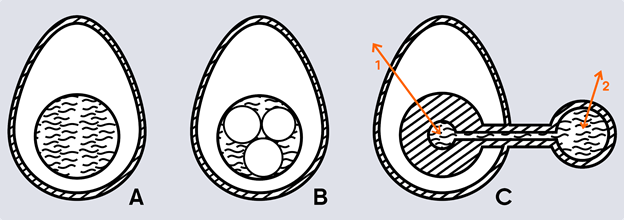

Figure 1

In Figure 1 there are three imaginary examples of the structure of personal intimacy. Example A has 3 layers, a hard crust on the outside, the lighter egg white and the dense deepest layer, the yolk. Our state of self is allocated somewhere in one of these layers and it moves in and out of them. For every individual, their main structure of intimacy may remain similar, being altered by accidental circumstances. In case B there are three internal lighter compartments within the yolk, presumably to deal with three different aspects of the deepest state. In case C the most inner layer creates an external appendage, the hard crust is pulled out of the main structure. In this case there are two ways to access the center of intimacy, #1 by gradually going layer after layer, or #2 by abrupt means. This happens when, for example, our state of being could rapidly change from being defensive to being vulnerable if an unexpected condition is met.

Our domestic space also has layers of intimacy, depending on how the rooms are arranged, they feel different, a bathroom inside a room is more intimate than one in a common area. Deeper in the private rooms there are personal cabinets and pockets. Every detail of the place we inhabit determines how we relate to our cohabitants and ourselves: windows, curtains, electric wiring system, light settings. Its arrangement determines how we define and limit the levels of confidentiality. Our own room is the place where we wake up after a strange dream, the place where we rest our body after dealing with daily ventures. The quiet place that is the empty shell of our being, as Bachelard mentions: “the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.”1

The nephrologist and writer Edith Farnsworth had a particular idea of how she wanted her ideal house to look like. She commissioned the modernist architect Mies van der Rohe to build a house with glass walls. The Farnsworth House was under construction between 1945 and 1951, in what was then rural Illinois. Edith’s desire to be alone in a transparent house without interior walls, isolated in nature, became a myth in itself. Her visionary commission was the beginning of the glass houses boom in America. Even before the Farnsworth House was completed, the American architect Philip Johnson had already finished his Glass House in 1949. Located in rural New Canaan, Connecticut, Johnson’s house was a success of domestic engineering. The house is heated from below, the copper pipes under the brick floor keep it warm during the cold winter, an inner cylindrical structure serves as bathroom and fireplace.

Philip Johnson’s Glass House

The fantastic idea of living in a single large glass room surrounded by the forest was for Edith very different to the physical experience. The Farnsworth House was very cold during the winter and its permanent transparency to the outside was not pleasing, about this she recalled: “Do I feel implacable calm?…The truth is that in this house with its four walls of glass I feel like a prowling animal, always on the alert. I am always restless. Even in the evening. I feel like a sentinel on guard day and night. I can rarely stretch out and relax.”2 In the reconsideration of her own fantasy, Edith wrote interesting testimonials about the effects of architecture on imaginative states of being and inwardness.

The eccentricity of building a glass house is not relevant in itself. Although it could serve as an example to recognize three different configurations of intimacy. These three configurations will help us think about how the interior-exterior relationship is altered by particular lighting conditions. One of the configurations of the Farnsworth House occurs during the daylight, when the house is a transparent cube, visually open to the exterior, both interior and exterior see each other in equal opacity. The second configuration is at night-with-the-interior-lights-on, where the inner side of the glass becomes a mirror, returning to Edith the reflection of the room. This configuration represents greater fragility for the resident, while someone from the outside could see the interior of the house without being seen, the exterior is an invisible black void. The third configuration happens during the night-with-the-interior-lights-off, where the house and the exterior are almost invisible for each other and they can both only see the nocturnal sky.

Just as a tragic movie can help us imagine what to do when someone deceives us, architecture could help us imagine how we want our internal world to be. We don’t need to build a desired house, just a fictional idea of it in our mind could help us imagine how to inhabit our internal space. Later, that image can help us think about what forms personal intimacy could take. In an interview with Michael Silverblatt, John Berger talks about fictional literature: “books and stories can help us to know how to carry ourselves, what stance to take in front of situations”, later he added: “The books that means most to me are the books that teach us subversion, subversion in face of the world as it is, books suggest the honor of an alternative.”3 Images of architectural spaces could be used to project scenarios for our inner voice and explore how to shape our future behavior. After an experience of violent trauma, this is something that needs extreme attention and crafting in order to make personal intimacy present in our lives again. And it could guide us in the process of being alone, in the suspension of our own being.

*

Ania is a visual artist and writer born in Cuba and currently living in the United States. She has travelled and worked in Santiago de Chile and other cities in South America. As part of her practice, she collects videos of people performing simple tasks, she interviews them about the way they move their body while doing their jobs and how a repetitive task changes them. She interrupts people’s meals to ask them to recreate an activity, using the food and the cutlery around. Since the pandemic started, she has been editing videos and writing at home.

1: Gaston Bachelard, “The poetics of space”, (1958)

2: Joseph A. Barry, “Report on the American Battle Between Good and Bad Modern Houses,” House Beautiful 95 (May 1953)

3: John Berger in conversation with Michael Silverblatt, Lannan Foundation (2002)