Out of the Night that Covers Me

- Bobbie Groth, Nightingale

Bobbie Groth is a familiar voice to Awakenings. Her funny and touching memoir, Gifts From Her Table, is currently being serialized with Awakened Voices. She also has visual art work in our gallery as a part of the current Our Bodies Remember exhibit. Now, Bobbie contributes a powerful essay about her process of healing and the significance she finds in art as a tool to provide relief and spiritual support. She describes a familiar journey for many survivors while generously including her wisdom and passion.

Out of the Night that covers me: The Creative Arts of Healing

by Bobbie Groth

I do not believe that any of the things we have to do to survive and heal from abuse are gifts, any more than the horrible wounds themselves are gifts. They must just be endured. Creativity is, however, something that some survivors use to assist themselves in healing from abusive experiences. I am one of those survivors.

Although we do not usually stay in the raw trauma of abuse forever, our relationship to the crisis changes over time. But it’s always there. Forever. I’m not going to suggest I have some sort of expert advice, because I don’t, but I will say that I have noticed how my own creativity-something I was born with-was greatly impacted by abuse. My creativity changed me from within as I used it in various ways to heal from those injuries.

You can never go back to the well-being that could have been yours before the experiences of abuse robbed you. Healing is a process, not an accomplishment. That very quality makes healing sexual trauma one of the cosmic things-it is a profoundly spiritual process.

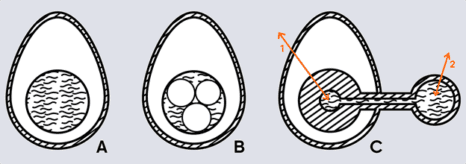

Some of the aspects of what survivors need include safety, therapy, self-reflection and the “scar-tissue relief” of self-soothing while the body and mind heal. When I shattered my right leg in a hiking accident, my surgeon talked a lot about “the bones knitting” and the need for time and lack of further injury for them to do so. I had a metal plate, eight screws, two pins and most of a year in a wheelchair to help me with that process-things that were anything but soothing or comforting, but without which my leg would never have looked the same, nor been useful, again.

I like applying that metaphor of “knitting the bones” to how creativity has intertwined with my own healing. Actual knitting can keep you warm despite the fact that it only creates permeable things-a knitted item is simply a series of loops of yarn. It’s counter-intuitive that knitted garments would be warm.

Equally paradoxically, creativity can help you knit the bones of your soul together again after experiences of abuse. Using the raw materials of the abuse can mean reawakening the hurt, but the act of creating art with it can keep you warm nevertheless. We use the traumatic memories as raw materials to externalize our suffering so that it is not secret anymore. By doing that we exert control over the trauma, which transforms it into strength. When it was the experience of abuse we did not choose it, and it was in control of us. By making art, we have reversed that and brought the anguish into the light.

I was born, apparently, with the desire to make art. I was also a victim of sexual abuse from a very, very young age. There were periods in my life where a dark night covered me and I held my fragile self together with brittle bands of denial, depression, and suppression. Those three things made creativity impossible and I could not do art. They were terrible times because I could not afford myself the freedom to do even the littlest thing to break free of my pain, for fear I would fly apart at the seams in doing so.

Then there were times when I hurt so badly I had to either do art or explode. This usually came after I had at least some modicum of affirmation from the world outside me-a recovery group, a friend, a loved one or books-that told me I was not alone and most importantly, that I was capable of both being wounded AND being strong. When I realized that, the next stage was anger, and with anger came an explosion of creative energy. Along with the fury to name my trauma and anger my “artist’s block” was released into a tangible outpouring of paintings, sculpture, poetry, stories, needlework. Anything that let me convert my pain to something that illustrated my trauma gave me control over that trauma’s very existence.

This kind of art I did just for myself. I had no desire for others to see it for a very long time, although when people did see it, it seemed to mean something to them. I found in art a way to take the terrifying images and experiences out of my head, where they were locked in a feedback loop of re-injury, and hang them out in the open where I could have some distance from them. I often chose as my subjects the lives of others whose stories told me I was not alone. By creating in response to their stories, I was also telling a little bit of my own story-just enough to provide relief to me without making me feel impossibly naked and vulnerable.

For me and so many other survivors, the recent #MeToo movement that exposes the routine evil of sexual abuse in our culture means we can show what was once our shame and fear, but now it is our voice triumphant. Hanging our words, paintings, drawings, sculptures, music, and every other creative endeavor in which we document our sexual injury in the open is the very thing that will help prevent it from happening to others. And that in itself is healing-a very spiritual thing.

***

Before retiring Rev. Dr. Bobbie Groth was an advocate and spiritual counselor to victims and perpetrators of violence for over twenty-five years. Bobbie’s avocation has been in the arts, primarily in painting, sculpture, writing, and playing traditional Celtic fiddle. Follow Bobbie’s blog at